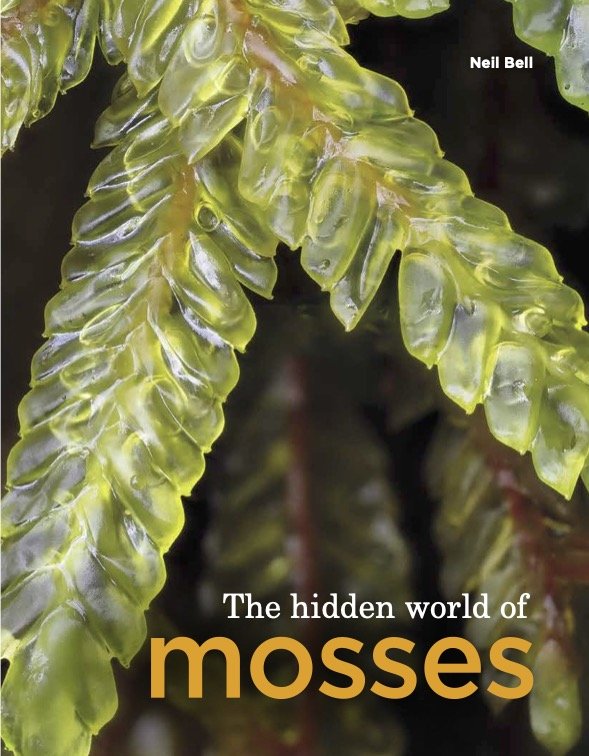

Episode 273: the hidden world of mosses

Sphagnum spore capsules. The lid detaches explosively, shooting the spores into the air. Photograph: Des Callaghan/The Hidden World of Mosses.

Subscribe to On The Ledge via Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Player FM, Stitcher, Overcast, RadioPublic and YouTube.

TRANSCRIPT

[0:01] Jane Perrone

If you're a gardener, you'll know that bare soil is the enemy of fertility, and that's where cover crops come in, and thanks to show sponsors True Leaf Market, we have you sorted for cover crops this autumn. True Leaf Market have been selling heirloom and organic garden seeds since 1974, and they've got a great selection of cover crop seeds, including their all-purpose garden cover crop mix, the most popular cover crop they sell to home gardeners. No idea where to start with cover crops? Well, True Leaf Market has a free PDF guide to cover crops. Just visit trueleafmarket.com and search for cover crop guide. You can order your cover crops online now at www.trueleafmarket.com and use promo code OTL10 to save $10 on orders of $50 or more. So visit www.trueleafmarket.com and enter OTL10 for $10 off your first order. Check out the show notes at janeperrone.com for more.

[1:15] Music.

[1:34] Jane Perrone

Hello and welcome to On The Ledge Podcast. It's episode 273 and I'm feeling mossy.

[1:42] Music.

[1:48] One of the meanings of the word mossy is 'antiquated'. And yes, that is how I am feeling. It's coming towards the end of the school summer holidays here and the house is a tumbleweed infested wasteland with the occasional apple core and half-drunk glass of milk kicking about. What can I say? Not to say that I don't love my children, but I will be looking forward to them going back to school and college. Thanks for all the feedback on the last episode 272 on plant trials. When I told my daughter about what plant trials are, she told me it sounds a bit like the Hunger Games. I'm not going to lie, I hadn't thought of it that way, but yeah, there will be Tillandsias fighting for their lives as we speak. And I'm heading back up to Walton Hall to do some more plant trialing and also to interview Don Billington of the nursery Every Picture Tells a Story. So upcoming Tillandsia info will be arriving in the show in the next few weeks. But let's get on to this week's show. And I'm talking about The Hidden World of Mosses with Dr. Neil Bell. Now this is the title of Dr. Bell's new book which, takes that very misunderstood group of plants, the mosses, and looks into what they do, why they're so incredible and where you can find them. And I was delighted that Dr. Neil Bell, who's a briologist, that's a studier of mosses, at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, joined me to talk about all things moss-like. Dr Neil Bell, thank you very much for joining me. You're a bryologist. I guess we need to start by finding out what a bryologist is and what you do, if we can start with that one.

Neil Bell

So yes, a bryologist is someone who studies mosses and also liverworts and hornworts. So these three groups of land plants, mosses, liverworts and hornworts, are together called bryophytes. And unfortunately we don't really have a common word that everyone knows that stands for mosses, liverworts and hornworts together, so bryophytes is the best we can do. But basically it's mosses and plants that are related to mosses.

Jane Perrone

Now your book, The Hidden World of Mosses, is great because there aren't that many moss books out there, let's face it. I'm embarrassed to say that my moss knowledge is very limited. I can think of one moss name off the top of my head, which is of course sphagnum. Why are mosses so, underrated? I guess we should ask first. Let's break down the differences between those different types of mosses that you mentioned, the liverworts and the hornworts. What's the categorisation?

[4:43] Neil Bell

Yes, so basically until quite recently we thought these were separate groups of land plants, mosses, liverworts and hornworts. We always knew they were similar and they had a similar lifestyle but we thought that perhaps some of these groups were more closely related to other land plants than others. And it's really just in the past 10 or 15 years that we've come to the conclusion that what we actually have is a natural group, mosses, liverworts and hornworts, or bryophytes together, are a group of green land plants that split off from the lineage which led to all the other land plants that we know today, that's the the ferns and the conifers and the firring plants, probably about 500 million years ago, and they've been doing their own thing ever since. So they're just a different group of terrestrial green land plants with a different way of living. And nonetheless, they're actually very diverse. So there are about 20,000 bryophytes in the world. So they're actually a very important group.

Jane Perrone

Yeah, absolutely. Mosses are, people are always trying to get rid of mosses, aren't they, from places, lawns and stones. But I do actually love a bit of moss. I think it's, they're wonderfully tough and often beautiful. I mean, is that something that you really get to appreciate when you're studying mosses and you're presumably down on your belly or looking up. or in odd places to find these things I'm imagining there's a lot of hidden beauty there.

Neil Bell.

Yeah, absolutely. And in fact, I mean, you're asking why mosses are so underrated. It is just the scale, I think, that's underlying that. So mosses are small plants. So they're not what you'd actually call microscopic. So you can actually see them with your naked eye, especially with a hand lens, a sort of magnifying glass, if you want to look at them more closely. But they're not so big that we're aware of them when we're just going about our everyday business. So not like flowers or trees where they're basically they're impinging on your consciousness when you're walking around. With mosses you actually have to make an effort to look more closely and it's that fact that they're sort of in between that microscopic and macroscopic world I think that makes mosses and moss diversity so underrated and ignored. But yes, to see mosses properly or to see other bryophytes properly you have to you have to look closely, you have to make an effort. And that's what I hope this book is going to do. It's going to get people down on their knees or looking at wall tops, looking at this green stuff that you see around them and trying to see that actually what looks like just a single substance is actually a collection of many different species of mosses and liverworts.

Jane Perrone

Mosses seem to be incredibly tough. They're growing in the most inhospitable circumstances with very little in the, what seems very little in the way of resources. They're not sitting in, oftentimes on a wall. How are they actually surviving in what seems to be quite extreme conditions?

Neil Bell

So mosses have a different way of living from other plant groups. And this is sort of, it's almost as if when mosses split off from the rest of land plants about four or 500 million years ago, They decided to take a different approach to ecology and to living. So, so bryophytes don't really have a vascular system. They have a very limited vascular system. That's these sort of tubes and things that convert, that transport water and nutrients around the bodies of other plants. Mosses and liverworts really lack this. So they're largely just getting their water and their nutrients from over the entire surface of the plant. And they don't have roots. So they're not taking water up from the soil. And to some extent, they're ebbing and flowing with the availability of water and nutrients in their environment. So it's sort of a different strategy. So that means that on the one hand, they do very well when there's lots of water available, because if there isn't water available, they'll just dry out. So they need a constant availability of water to actually do well and to keep metabolizing and outcompeting other groups. At the same time, because they're ebbing and flowing with the availability of moisture environment, they have to be very good at drying out as well. So mosses are very good at resisting desiccation. They can dry out and remain in a dry state, often for weeks of time and then come back to life in a sense when there's more water available. So one sort of phrase that's often used to describe mosses ecology is drying without dying. So it's almost paradoxical. We think of mosses as loving wet places, and that's true, but at the same time they're also very desiccation tolerant. And this goes hand in hand with lacking a vascular system and with this lifestyle that we call poikilohydric, and it's really what distinguishes bryophytes from the other groups. And it also means that they can take over at quite a low metabolic rate, so they can survive in places perhaps where they're not able to grow for for large periods of the year, such as snowbed habitats in the mountains where perhaps the ground is covered in snow for many months of the year. And it also means that because they don't have roots, they can grow on surfaces, on substrates, which other plants can't, like directly on rock. So you won't see many vascular plants or other more familiar green plants growing directly on rock but many bryophytes are able to do this.

Jane Perrone

So you must be incredibly knowledgeable about many, many moss species, are there any sort of standout mosses that you love telling people about who are maybe looking at you, wondering why on earth you've dedicated your life to the study of mosses. How can you turn somebody into a moss fan?

Neil Bell

So there are many, so in Britain we have about 1,100 bryophytes, that's mosses and liverworts and some hornworts, and in Scotland we have most of these, about a thousand. So part of appreciating mosses and liverworts is just to appreciate that diversity, but of course there are some that I'm particularly keen on. So we have some amazing mosses. There's some in the family Splachnaceae, it's a strange word, but it's a family of mosses. And this includes mosses which attract insects to disperse their spores, which is something that really only happens in that particular family of mosses. So these mosses will produce spore capsules with giant umbrella-like projections, which almost look like mushrooms, and they grow in places like Scandinavia and Canada. We get some species in this family that also grow in Britain, they're not quite so dramatic. And these mosses will attract insects, tiny flies, with these brightly coloured mushroom spore capsules, mushroom-looking spore capsules, to disperse their spores, which are actually sticky, so they'll stick to the fly, and the fly will collect the spores and then fly off and deposit them in somewhere that this moss can then grow. So these mosses, species like Splachnum luteum, will grow on dung, so that's why they've developed this ability to use insects to disperse their spores, because they need to find some method of getting from one bit of dung to another bit of dung. And this is obviously something which requires a bit of help. So yeah, so the Splachnaceae are very, very dramatic and an interesting species. I'm also quite keen on mosses which grow in particularly in southern temperate areas, which almost look like miniature trees. So we have these mosses that we call dendroid. And dendroid basically means tree-like. And if you can imagine a miniature tree, a tree that's about five or 10 centimetres tall, then that's really what these mosses look like. And they're that shape for the same reason that the trees are that shape. They're trying to get their photosynthetic tissue above the other smaller plants that are growing around them. So yeah, these are some of my favourite bryophytes. But really there are many. So I could go on and talk about favourite mosses for days.

[13:15] Music.

[13:24] Jane Perrone

More sterling moss to come, but a bit of housekeeping now, and I wanted to give you a quick Patreon update. This is my crowdfunding platform, and a shout out to Jon who took up my offer of a free trial at the ledge end level. Patreon, if you're not aware, is the way that I get support from people on a monthly basis, so every month you pay a small amount, and in the case of the two higher tiers you get extra bonus stuff like the bonus podcast, an extra leaf, my Christmas mailout and if you're a Super Fan, which is the top tier, you'll soon be getting access to an audiobook of my new book, Legends of the Leaf. So lots of reasons to sign up. Thank you to John. Madeline has also become a Ledge End . Janet has upgraded from Ledge End to Superfan - and Janet is the wonderful life force behind the Cambridge plant shop Small and Green. Do check them out at smallandgreen.com. So Patreon, it's out there and details on my website janeperrone.com if you want to find out more about that. If you want to support the show in other ways you can leave a review and that's exactly what Ashleyrose83 and Oshdeginense, that's a, not quite sure what that name is, but they both left reviews and I was extremely grateful. They said nice things about the book and the podcast and that both lifts my spirits and helps other people to find the show. The other piece of info that you should know is that my next project, Houseplant Gardener in a Box, is coming. I've just put details of it up on my website and if and if you go to my Instagram or TikTok, which are now both @j.l.perrone, you'll find an unboxing video of me, checking out this new, amazing product. Very giftable, if I may say so. A set of 60 cards and a booklet about houseplant care, helping you choose the right plants for your home. You could also use these as decoration. You could hang them on your wall.They are beautiful enough to do that. So it's a really lovely set, which I do hope you'll check out. And the details of that are at janeperrone.com or check it out at @j.l.perrone on Instagram and TikTok. It's out the end of September in the US and the 11th of October in the UK and should be available everywhere. So that's great news. And also don't forget to sign up for my newsletter, The Plant Ledger. I should say in case you haven't done so so far because you think, well, it's just going to be newsletter version of the podcast. It really isn't. There's loads of information in there you won't find in the podcast. A listing for houseplant events in the UK, a news section which I'm now making international with little flag emojis so you know which country it's relevant to, featured follow so you can find new and interesting people to follow on social media who are planty, and loads more. So do go and check that out. Again, all the info on the website at janeperrone.com and I'd love you to subscribe.

[16:38] Jane Perrone

It's time for a short and sweet Q&A this week. I can't remember specifically who asked me this question. I think I've had it a few times, but people were asking what a TDS meter is and whether they need one. TDS meters, have you got one? Do you use it? And what on earth does TDS stand for? Well, it's Total Dissolved Solids. And this is a meter that you use in water to test water before you give it to houseplants. And you'll probably be able to pick one up for between, I don't know, five and $10 or pounds online fairly easily. If you've never seen one before, they look a bit like, I don't know what I could compare it to. They look a bit like a thermometer, a digital thermometer that you might use when you get sick, and very much small enough to pop into your pocket and they have a digital readout so you can just pop them into the water that you want to test. There's kind of some nodes at the end which you just pop into your water and you'll get a reading for the parts per million. So what are they measuring and do we need one? Well the dissolved solids in water are made up of mainly two things. A bit of organic matter, so particularly if you're using say rain water, organic matter might make up for a larger proportion but generally the organic matter is quite small and insignificant. The main part is what we call mineral salts and this is made up of stuff that you find generally in tap water that is put in there as part of the treatment process and also can vary depending on the geology of where you live and what's happened to the water. So we're talking about things like potassium, sodium, calcium, nitrates, chlorides, and sulfates. So if you tested distilled water, there should be no dissolved solids in that water. So your TDS meter should show zero. And what is that number actually referring to? Well, it's PPM parts per million. So generally speaking, if you had drinking water, you'd be looking for parts per million that were under 300 and if it was really good drinking water you'd expect it to be round about the 100 mark and that would mean 100 parts per million so if you've got a million particles 100 of them are consisting of dissolved solids. So the kind of people that often have TDS meters are people that are growing carnivorous plants because carnivorous plants cannot cope with a lot of mineral salts in their water. So if you're growing sundews or venus flytraps you want a kind of a maximum ppm probably of about 50 the lower the better really. And you would want to test your tap water and see whether your tap water could actually offer that. If it doesn't then you might be looking at either collecting rainwater using distilled water or getting a reverse osmosis water, either from your own system or from an aquatics shop. Now, the measurement you're getting here, I should say, is different from the pH, the acidity or alkalinity of the waterhose are two different things. So the TDS meter is not going to tell you that, and we can cover testing pH in another Q&A. But what about other growers? If you're not growing carnivorous plants, do you need to bother? Well, I think it's one of those things that's handy to have. It's interesting to be able to measure and compare your water against other sources of water like rainwater. It's not essential, I would say, but it's an interesting addition that I would certainly add to your houseplant toolkit if you can. So I hope that helps whoever it was that was asking me that question about TDS meters. And if you've got a question for On The Ledge, drop me a line on theledgepodcast at gmail.com. Right, it's time to get back into the world of soss and warning, you're going to need your hand lens.

People like me who are into houseplants, if we are pushed for a type of moss, to name a type of moss, we're going to say sphagnum. And I'd imagine before today, I probably thought that sphagnum moss was a single species, but I think you're going to tell me that it's a little bit more complicated than that. Can you tell us a bit about sphagnum moss and where and how it grows and how many species there are?

[21:24] Neil Bell

Yeah, so sphagnum is not a species, it's actually a group of species, it's what we call a genus. So there are about 400 species of sphagnum in the world, and in Britain we actually have about 40, which is quite a large percentage of that number. And the reason we have so many in Britain is because these plants are particularly adapted to bog habitats, so what we call peat bogs in Britain. So these are sphagnum mires. They're habitats which are dominated by sphagnum moss. And the reason for this is because the sphagnum itself creates the habitats in which it can do best. So sphagnum moss does very well in very wet places and in quite acidic places.And as a result, it tries to keep the habitat in which it's growing wet and acidic so that it can outcompete other plants that might get in there, like horrible trees and things that which will take all the water out of the soil. So sphagnum does this largely by its ability to store huge amounts of water relative to its size. And of course, this is what makes it useful for horticulture because it's incredibly spongy, absorbent substance when you are either living or dead. But it's able to do this because if you actually look microscopically at the cells inside a sphagnum leaf, you'll see that there are two different types. So one type of cell is the normal green photosynthetic cell that's doing all the metabolic work, but these are actually quite small in relation to the size of the leaf and most of the volume of a sphagnum leaf is taken up by these other types of cells which, when the plant is mature, are empty and dead. And these are basically acting as almost like giant water bottles, as receptacles to hold water. So if you can imagine a sphagnum leaf as being a matrix of photosynthetic cells and then water-absorbing cells, that explains why they're able to hold this huge volume of water relative to their size and keep. The habitats in which they're growing continually moist. They also keep the habitat in which they're growing acidic because they actively pump protons, that's hydrogen ions, into the cell and that keeps the soil acidic. And this means that over hundreds of years, if you have a living carpet of sphagnum growing in a bog habitat, it actually inhibits decomposition because it will, by keeping the soil permanently waterlogged and permanently acidic. That's inhibiting the normal breakdown processes that would break down dead organic matter and release the carbon that's in that organic matter into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide. So that's what peat is. Peat is undecomposed dead sphagnum that has built up over hundreds, sometimes thousands of years. And it's incredibly important in terms of climate change and global warming, because that peat that's in the soil there is, a very important carbon sink. So it actually represents something like about 40% of the carbon that's stored in natural environments and terrestrial habitats is actually in the form of peat. So if you can imagine that carbon started to decompose and that was then released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide, that would be a major contributor towards the acceleration of climate change and of global warming. So that's why the maintenance of that living sphagnum layer on top of peat bogs is incredibly important, because it's that active living layer of sphagnum that's keeping the sphagnum bog habitat moist and keeping that carbon locked up into the soil and stopping it being released into the atmosphere as carbon dioxide.

Jane Perrone

Also you've got that ecosystem that's developed around. Other plants that have managed to survive in those kind of acidic conditions as well. So it's a really unique ecosystem, isn't it? The peat bog, as you say, massive carbon sinks, so important to retain that. And I guess this is why On The Ledge we've been, well, I've been banging on about peat-free for as long as the podcast has been going. So yeah, it's great to hear the actual reasons why we should be preserving those peat bogs.

Neil Bell

Absolutely. Any more sort of sphagnum moss facts? I mean, of the sphagnum moss species, are there any ones that particularly are standout or particularly interesting?

[26:15] Neil Bell

There's one in particular which is very attractive. There's one called Sphagnum squarrosum, which is these little sort of bent back leaves that are almost reflect completely over on themselves. So the entire plant looks a bit like barbed wire or something like that. Many species of sphagnum are quite large and quite juicy looking. So the ones that would be dominant on really good quality peat bogs, things like sphagnum papillosum, they're really quite dramatic plants, but others are quite small. So some species of sphagnum, even ones you also get in bogs, are small, but they can be very brightly coloured. So they're reds and they're oranges and yellows, many sphagnum species which are beautiful and different in their different ways. They are actually in many ways quite similar to each other in terms of how they differ from other mosses. So sphagnum as a genus is a member of a family called the Sphagnaceae, and that family is quite isolated from the rest of mosses. So they're quite different in their morphology structure from the rest of mosses. But having said that, most species of sphagnum are quite similar to each other. And that's because in evolutionary terms, that group that sphagnum is in split off from the rest of mosses quite early. But actually, most of the species of sphagnum that we have now have arisen quite recently. So if you can imagine a big, long branch of evolution persisting for hundreds of millions of years, with lots of species arising and then going extinct, and then maybe there was just a relictual group from that very ancient lineage, from which the diversity of Sphagna that we now have evolved relatively recently. So yeah, they're a very interesting group.

[28:12] Jane Perrone

Well that is fascinating to know and certainly I'm glad that I now know that sphagnum is a genus and not a species. I was also fascinated reading your book about the group of liverworts that are carnivorous. Again, had no idea. Can you tell us a bit about the carnivorous members of the liverworts?

Neil Bell

Yeah, so I have to sort of qualify this to begin with and saying it's not really proven yet.

Jane Perrone

OK.

Neil Bell

We assume that some liverworts are or may be carnivorous to some extent, but it's quite a difficult thing to prove in fact. And it's more than, if it is happening, then it's happening in more than one liverwork group and probably it's evolved independently. But the reason we're not quite sure is because these adaptations, which look like they could be associated with carnivory and quite possibly are, could also have arisen for other reasons. They could just be for storing water. So what this looks like is that we have these tiny pieces of liverwort which have leaves. And then part of the leaf that is on the liverwort is actually modified into this very specialist structure which looks like a big sort of flask, if you like. If you imagine a sort of sphere that's open at one end. And this is part of the leaf. But obviously, what it does is it can hold water and keep water inside itself a bit like a giant cup, if you like, with a very small entrance at the top. And there are some groups in which not only do they have these flask-like modifications of leaves, but there's a sort of little flap on top of the flask, so a little door, if you like, into this tiny chamber, which hold water. And this sort of trap door, if you like, appears to work in one direction, so if you push on it in one direction, you'll get in, but then you can't get back out again. And we can look at these lobules, as they're called in liverworts, and we can see that they do trap microorganisms inside them, so things like protists and rotifers. And of course, these, if these are in there, then there's a, it would make sense if, if these are to some extent being digested and if the nutrients that are, are inside these tiny animals which are dying inside the liverwort were being absorbed into the, into the plant. And we do find that these liverworts are often growing in nitrogen poor environments, which of course is exactly the situation we find in vascular plants where we get carnivory, so things like sundews and venus flytraps which which trap insects for carnivory and for usually for almost always for nitrogen. It would make sense if these tiny liverworts are doing exactly the same thing, just on a much smaller scale, except with microscopic animals such as protists and rotifers. But it's still to be proven, unfortunately.

Jane Perrone

Well, I mean, I imagine, as you say, that's quite hard to study. It's not the easiest thing. It's not like watching a Venus flytrap close. It's not the same scale.

Neil Bell

Yeah, you can show, for instance, that certain plants perhaps have higher ratios of certain, for instance, nitrogen isotopes, you can show that perhaps that's one way of approaching it to see, because if these things are being carnivorous, then they should have changed ratios of nitrogen isotopes and things like that. So that sort of study is actually underway now and we may find out quite shortly, we may get definitive proof whether or not these liverworts are carnivorous or not.

[31:47] Jane Perrone

If people are listening to this thinking, well, I never knew that there were so many mosses and they were so interesting, any guidance for us moss newbies as to where we should start looking for them in our daily lives and how to kind of learn more about mosses?

Neil Bell

So the great thing about mosses and the other bryophytes, the liverworts and the hornworts, is they're really all around us. So because of these attributes of their ecology I was talking about earlier, because they're able to grow in almost anything, and because they're able to resist desiccation, and because some of them are even able to resist atmospheric pollution, even though others are very sensitive to it, we can find them almost anywhere. So we can find them in cities on the tops of walls. You've probably seen just walking around your local neighbourhood, even in an urban environment, that you'll get this green stuff on tops of brick walls or on on top of stone walls. And you probably know that's moss, but you probably don't know that there are probably five or 10 species anywhere you're seeing moss growing on top of a wall or a brick wall or a stone wall. You've probably got many different species mixed in together. So really it's just a case of getting down there and looking closely. And first of all, just starting to be aware that what you're seeing is actually different species growing together, a community, rather than just a single amorphous substance. And to do that, you ideally, especially if you're like me, maybe a bit older and your eyesight close up isn't as good as it was when you were 20, you need some kind of help to do that. So most virologists will carry around this sort of small magnifying glass that we call a hand lens. It's sort of something you put around your neck and or you can keep it in your pocket. And it's a tiny magnifier. So if you have one of these, you can just, it opens up this new dimension, which can make you aware of this hidden diversity of these tiny plants around you, which you previously perhaps were only vaguely aware of in the periphery of your your consciousness, if you like. So yeah, I recommend anyone just looks more closely and gets a hand lens. Secondly, there are groups. So we have in Britain, the British Bryological Society. So there is an association of academic and amateur biologists who hold meetings and that's particularly helpful when you're beginning to just go out in the field with other people that know these plants very well and to be just be shown them individually and to be told what they are because initially it's quite difficult to identify bryophytes as species and it helps to have someone showing you and actually confirming that what you think is one particular species is actually. But really urban environments are a good place to see bryophytes. Obviously woodland is a great place to see bryophytes in most parts of the world and particularly wet woodlands. So woodlands which are sheltered in narrow valleys or if you happen to live in a wet part of the world maybe near the coast. Anywhere where there's is either you have a lot of precipitation throughout the year or whether or where due to the topography the woodland is sheltered if it's in a valley or something like that and therefore retains a lot of moisture. These habitats are usually, at least in temperate areas, abundant with many different species of bryophytes. Of course, mountains and bogs and heathlands as well are great for bryophytes if you can get to them. But yes, so get a hand lens and try and meet up with local people in your area who are interested in mosses.

Jane Perrone

Well I'm glad you mentioned the hand lens. Anyone who's listened to my show before will know that I love a hand lens. I'm often telling people to get a hand lens not just for mosses but any plant is fascinating to look at. Hopefully there's lots of hand lens converts already listening to this but yeah ideal for mosses. It really opens up a new dimension of life to you really and it's not just mosses but as you say parts of plants so you can see stamens and flowering plants and other sort of small parts of other plants and of course insects and and lichens and other things. So really you have that layer of diversity and of wildlife which suddenly becomes available to you as soon as you get a hand lens and start carrying it around with you. So I really recommend that to anyone. Well thanks very much for that insight into mosses. I am sure I'm going to be going out and looking around my garden and suddenly as it often happens with these things, suddenly our eyes will be opened and we'll be spotting mosses everywhere I suspect.

[36:31] Neil Bell

I hope so!

Jane Perrone

Thanks so much for joining me Dr Neil Bell.

[36:35] Music.

[36:42] Jane Perrone

Thank you so much to Dr Neil Bell and if you check out the show notes you can find out more information about the hidden world of mosses which is out now and will fulfil all your mossy needs. That's all for this week's show, I will be back two weeks hence, so I am wishing you a fantastically soft and springy landing, into the weekend and let me know how your moss hunts go. Bye!

[37:11] Music.

[37:35] The music you heard in this podcast was Roll Jordan Roll by The Joy Drops, The Road We Used to Travel When We Were Kids Komiku and Overthrown by Josh Woodward. The ad music is Nothing Like Captain Crunch by Broke for Free. All tracks are licensed under Creative Commons.

[37:53] Music.

I talk to bryologist Dr Neil Bell about the wonders of moss, and answer a question about TDS meters.

This week’s guest

Dr Neil Bell is a bryologist at the Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. Much of his research is focused on quantifying, understanding and promoting Scotland’s globally important bryophyte flora, of which mosses are part. Neil is also editor-in-chief of the Journal of Bryology. HIs book The Hidden World of Mosses is out now.

The British Bryology Society celebrates National Moss Day on October 21 2023.

Achrophyllum dentatum. Photograph: Des Callaghan.

QUESTION OF THE WEEK

I’ve had several inquiries about TDS meters and what they do - so here’s the lowdown. TDS meters measure the amount of Total Dissolved Solids in water - measured in PPM or parts per millions. TDS consist of mineral salts such as sodium, potassium and calcium plus a small amount of organic material. The amount of TDS in water depends on a number of factors - including the way it’s been treated, the topography of the land from which it came.

A TDS meter is about the size of a digital thermometer and can be bought for a few pounds or dollars. You can use it to test your water - from the tap, filter or rainwater storage - to see whether it contains a lot of mineral salts, or a little. It’s not really essential unless you grow plants that need water with very low levels of mineral salts, mainly the carnivorous plants such as sundews and venus flytraps which need TDS of around 50 PPM or less. Drinking water should have a TDS of less than 300 PPM.

Want to ask me a question? Email ontheledgepodcast@gmail.com. The more information you can include, the better - pictures of your plant, details of your location and how long you have had the plant are always useful to help solve your issue.

THIS WEEK’S SPONSORS

True Leaf Market

If you’re looking for a thrifty way to boost the health of the soil in your garden, cover crops are the answer. Tnanks to On The Ledge episode sponsors True Leaf Market you can rehab your soil the same way farmers do - by growing cover crops. True Leaf market have been selling of Heirloom and Organic garden seeds since 1974, and they offer a great selection of cover crop seeds, including their all purpose garden cover crop mix their most popular cover crop seeds for home gardeners. To get a FREE PDF of true Leaf Market’s beginners guide to growing cover crops visit trueleafmarket.com.

Order your cover crops online now at TrueLeafMarket.com, use promo code OTL10 to save $10 on your first order of $50 or more.

HOW TO SUPPORT ON THE LEDGE

Contributions from On The Ledge listeners help to pay for all the things that have made the show possible over the last few years: equipment, travel expenses, editing, admin support and transcription.

Want to make a one-off donation? You can do that through my ko-fi.com page, or via Paypal.

Want to make a regular donation? Join the On The Ledge community on Patreon! Whether you can only spare a dollar or a pound, or want to make a bigger commitment, there’s something for you: see all the tiers and sign up for Patreon here. Want to give it a try before you buy? You can take out a seven-day free trial …

The Crazy Plant Person tier just gives you a warm fuzzy feeling of supporting the show you love.

The Ledge End tier gives you access to one extra episode a month, known as An Extra Leaf, as well as ad-free versions of the main podcast and access to occasional patron-only Zoom sessions.

My Superfan tier earns you a personal greeting from me in the mail including a limited edition postcard, as well as ad-free episodes.

If you like the idea of supporting On The Ledge on a regular basis but don't know what Patreon's all about, check out the FAQ here: if you still have questions, leave a comment or email me - ontheledgepodcast@gmail.com. If you're already supporting others via Patreon, just click here to set up your rewards!

If you prefer to support the show in other ways, please do go and rate and review On The Ledge on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you listen. It's lovely to read your kind comments, and it really helps new listeners to find the show. You can also tweet or post about the show on social media - use #OnTheLedgePodcast so I’ll pick up on it!

CREDITS

This week's show featured the tracks Roll Jordan Roll by the Joy Drops, The Road We Use To Travel When We Were Kids by Komiku and Overthrown by Josh Woodward. The ad music is Nothing Like Captain Crunch by Broke for Free.