Episode 245: houseplant botany with Dr Scott Zona

Transcript

EPISODE 245: HOUSEPLANT BOTANY WITH DR SCOTT ZONA

Jane Perrone 0:00:13.6

Greetings, growers! It's your host, Jane Perrone, here and today we're stepping into the plant kingdom, accompanied by an expert guide - botanist, Dr Scott Zona. He's here to reveal some of the secrets of his new book "A Gardener's Guide to Botany' and I've got a response about Fluval Stratum for the Q & A section.

I've always been a great advocate of learning as much as you can about your plants, hence the botany strand of this here podcast, so I was delighted to get a copy of the new book by Dr Scott Zona, called 'A Gardener's Guide to Botany' and I liked it so much, I did a blurb on the back of the book for him. He's joining me this week to tell me all about the book, how we all need to venture deeper into the plant kingdom to understand our plants, but also because it's really super-fascinating and helps us look after our plants better, which is also really vital.

Scott Zona 0:01:28.1

My name is Scott Zona and I'm coming to you from Hillsborough, North Carolina.

Jane Perrone 0:01:32.8

Good morning, Scott! Well, it's very morning for you right now! Thank you for agreeing to talk to me about your new book, which I'm very excited about. It's called 'A Gardener's Guide to Botany.'

This is much-needed. I mean, actually, I should say from the outset, I'm actually quoted on the back cover, so I'm excited, and I do say this is the book I've been waiting for; this is a must-read for all gardeners who want to expand their knowledge of understanding the plants they grow. I stand by that. As anyone who's listened to the show for a while will know, this is one of the things I'm passionate about, is educating people about botany. I learnt loads from reading this book, I have to say, so I'm sure listeners will too.

Why do you think, though, that it's important for us? Like, me and other 'amateur' -- which I'm not sure about that word - but 'hobby' growers? Why do we need to know about this stuff in the first place and what kind of things can people expect to learn from your book?

Scott Zona 0:02:31.9

Well, I think, as with anything in life, knowledge is power. So knowing plants, knowing how they grow, knowing what they're doing, I think translates into making us better growers. At least that's my hope. Learning about plants connects us to our plants and I would also hope that it would connect us to the natural world in general -- the natural world outside our homes - because we need to care about that.

I also find that learning something, maybe it keeps me young. I learnt loads while I was doing the research and writing the book, so it satisfies some curiosity and I think that's a good thing.

Jane Perrone 0:03:21.0

Absolutely. As you say, if you can just understand what's going on with your plant and how the basic processes are working, it helps enormously, I find.

In the intro to the book, you talk about this idea of going into the plant kingdom and exploring it. I love that idea, that you could imagine yourself heading into this amazing plant-filled domain - kind of a metaphor, but kind of literally too. It strikes me that, for a lot of people, this is a mystery domain, a place where we don't necessarily know as much as we should. Have you come across any misconceptions along the way of teaching people about botany, about how plants work, that have made your eyebrows rise?

Scott Zona 0:04:08.6

Oh, yeah, loads! For me, it's hard to imagine not being interested in plants. I've been growing plants since I was six years old. But over the years teaching plant courses, botany courses, we'd be out, usually in the Botanical Garden, looking at plants, and I'd be talking about it and there'd be a dozen students, and they'd all be six feet back. This was before social distancing. They'd be way back there, and I'd be talking about the smell of the plant.

If somebody was telling me about the smell of a plant, my nose would be right in there. A couple of students would come forward and smell the plant, but most of them would hang back. They seemed very, I don't know, maybe fearful of the plants? I don't know. Out to get them? Poisonous? Delicate? I don't know. I think, for a lot of students, it takes a little effort to overcome this idea that plants are something you look at, but don't touch.

And then also, for some people, I think plants are just the green backdrop of life, and they don't look more closely at that until they start getting into botany. Then suddenly, this green backdrop comes into focus and they begin to see plants as individual plants and see them for what they are.

But yeah, I mean, that's hard for me to imagine being that way because I'm not that way. Whenever I go places, the first thing I look at is the plants and then, maybe, I'm looking at where I'm going and who I'm supposed to meet and all that! Being a lifelong plant person, I had to adopt a different mentality writing the book because I know not everybody thinks like I do.

Jane Perrone 0:06:11.1

Absolutely, yeah. I have nearly crashed my car several times while looking at plants. I'm not going to lie!

One of the things that I think this book is really strong on, is making what are admittedly quite complex concepts, for those of us who haven't studied botany at a high level, actually understandable. One of the things I really loved, was the way you use the metaphor of a Lego set for explaining the way that plants grow. Can you just explain that for our listeners?

Scott Zona 0:06:41.3

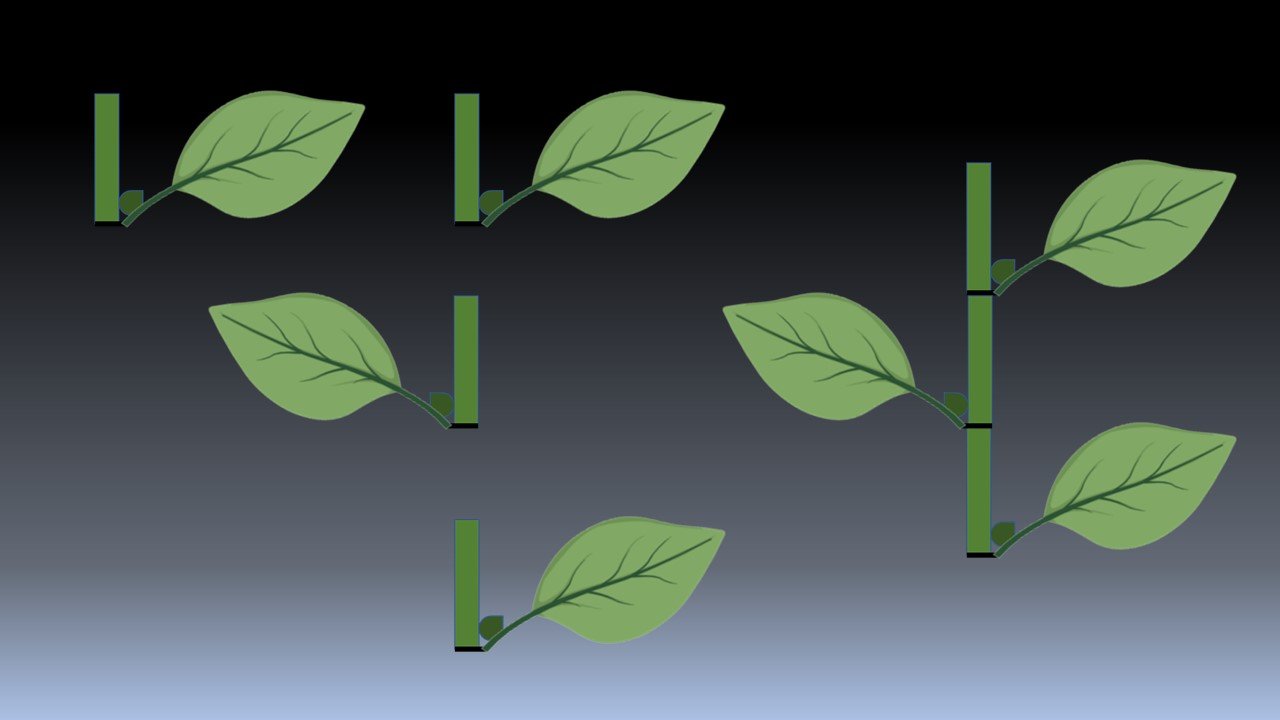

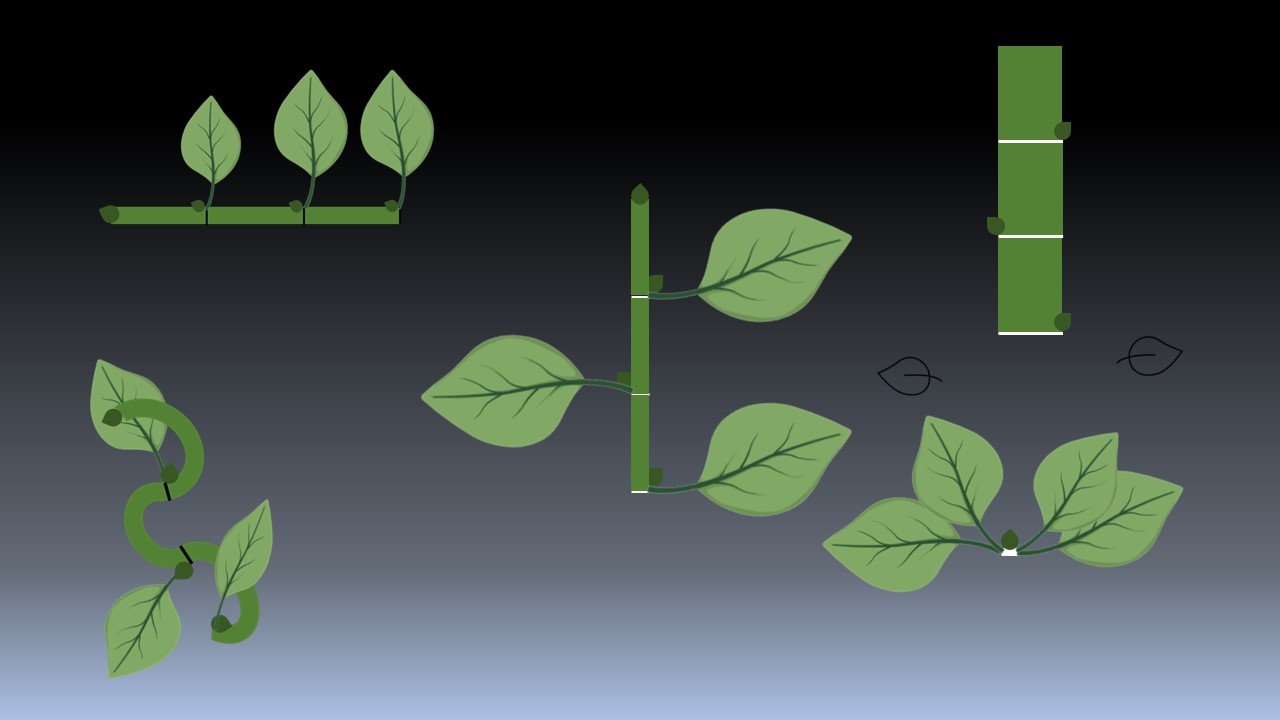

Yeah. Well, unlike animals, plants have a very different way of growing. We're all familiar with animals. We're all familiar with humans. We start out as small children, and we grow up, but we don't gain any more parts along the way. But plants aren't like that. Plants are built of repeating units, and that's called the phytomer. These repeating units can be just stacked up in ways basically like a Lego set, to build plants.

The unit is comprised of the node and the inner node on the stem, and then the leaf that's attached to the node, and then the actual bud which is that little, often dormant bud that sits there, down where the leaf joins the stem on the node and, basically, by stacking those up, you can make a plant, and then, by changing parts of it, you can make all the different kinds of plants. So if you shrink down the inner node so that it's essentially non-existent, then you can have, like, a rosette plant: so, something like an African Violet, or a Tillandsia air plant. Those are rosette plants, basically just rosettes of leaves.

Or you could just take the basic, generalised plant and remove the leaves, and then you've got a stem succulent, like Euphorbia, or cactus. Or you could put the stem on its side and then you have, like, a creeping rhizome on, say, a fern, maybe, or an orchid, a Cattleya orchid. The above-ground parts of a plant are built to these repeating units, but what is really interesting, is that the below-ground plants - the roots - are not built on repeating units. Roots can branch any which way they need to branch and they don't depend on that repeated unit, where branching occurs only through that axillary bud, that little dormant bud there, at the node.

So I think it's remarkable to me that there's these very different ways of growing both in the same plant: the above-ground parts are these repeated units, and the below-ground plants are pretty much free-form growth, and that a leaf cutting, for example, if you take a leaf cutting of an African Violet, it will put up roots and then eventually make a little plant, and that plant will grow on to make an adult plant. But that leaf cutting which is from the above-ground part of the plant has the ability to make the roots, which then behave like roots and grow below the ground. I find that very interesting. I don't know if other people get off on that as much as I do! I really think it's amazing!

Jane Perrone 0:09:51.4

I do too! Going on to roots, another phrase from your book that I really enjoyed was when you called roots 'the dark matter of the plant universe.' So true! We just don't think about those roots enough really, do we? I'm always telling people to look at the roots! So we've established they're not doing the same growth pattern as the above-ground of the plant. Obviously, they're taking in water and nutrients, but what are roots actually doing?

Scott Zona 0:10:20.2

They can do a lot of things. They certainly can take up water, nutrients, and that's one of their primary functions, of course, and then the other - probably I'd call it also a primary function - would be to support the plant. The plant has got to somehow support itself, whether it's in soil, or as an epiphyte, growing on, for example, on the branch of a tree. The root's there to hold the plant in place so it doesn't just fall over or roll around, whatever.

Absorption and support are the two primary, or main, functions, but then you get secondary functions, depending on the species. Some roots can be photosynthetic, for example. We know a lot of epiphytic orchids have photosynthetic roots, and the root tips are nice, bright green, or at least they should be if they're healthy roots.

Roots are important places for the manufacture of a lot of the important chemicals that plants normally manufacture, especially some of the defensive chemicals. So, for example, a Phalaenopsis orchid, a moth orchid, makes defensive chemicals that it puts into its flowers. Moth orchid flowers, phalaenopsis flowers, last a long time, typically, and in nature, of course, anything that is sitting around for a long time is going to be eaten by something. So the plants are putting a lot of their defensive chemistry right into the flowers, to keep those flowers from being eaten so that they can attract the pollinators and do their job. But the chemicals, the alkaloids that they're making, are manufactured down in the roots and then transported up into the above-ground parts of the plant and then, ultimately, the flowers.

So roots are important sources of chemistry inside the plant. Roots can also be storage. We know about storage roots, especially in plants from succulent areas. Sometimes you even see roots that are involved in defence. I can't think of any houseplants that do this, but certainly, there are some palms that produce little roots from their trunks, and these roots can grow up for a few centimetres and then harden off and become spine like. So you have root spines in some palms.

Those are, just off the top of my head, some of the things that roots are doing in plants, but you're right, they can do a lot more than just absorbing water and nutrients.

Jane Perrone 0:12:54.8

I'm getting a bit obsessed with fungi right now. There's a book by a guy called Merlin Sheldrake. I can't remember what it's called, but anyway, it's an amazing book. It's made me think really differently about interactions between roots and fungi and I'm wondering what's going on. It seems to me like we know maybe five per cent of what's actually happening with roots and fungi and their interaction so far.

Scott Zona 0:13:23.0

Five per cent might be generous, actually! Yeah, that's another thing why roots are really important, is that they are the place where a plant is interacting with all kinds of interesting micro-organisms, including fungi. That may not always be happening in houseplants, because, of course, houseplants are growing under, let's face it, very artificial conditions. It's not exactly replicating what's happening out in nature, but certainly, in nature, roots are really important for things like mycorrhizae or nitrogen-fixing bacteria. And then, also, lots of bacteria that are in fungi that are living just on the surface of the roots. They're not causing any disease or anything like that. They're living with the plant and they are beneficial to the plant.

There's a group of bacteria that I think I mentioned in the book, that are called plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria. So, plant growth-promoting, that's obvious, and then rhizobacteria, meaning rhizobium root. So these are bacteria that grow on the roots of plants and promote plant growth, which is pretty amazing! It's a hot area of research right now because I think botanists are beginning to realise that plants are not growing in isolation - even houseplants are not growing in a totally sterile environment - and that there's lots of things going on, especially down at the roots. We don't see them, we don't think about them, but basically half of the plant is there, underground.

Jane Perrone 0:15:14.1

Yeah, I think we've got so much more to learn and, as you say, I'm starting to see more mycorrhizal fungi products coming onto the market, to do with houseplants. I guess everyone's switching on to this. I don't know how successful they are. I'm guessing that it's a very blunt weapon, as it were, because each would have a very specialist set of interactions and species that they would be adapted to working with, but it's interesting that we're starting to move in that direction of at least thinking about that stuff now.

Scott Zona 0:15:47.2

Back when I went to college, which was 100 years ago, plant physiologists, people interested in the growth of plants, they'd maybe test the soil and the first thing they do is they stick a soil sample in a furnace and burn off all the carbon - get rid of all the carbon, all the organic matter - and then they test the soil for how much iron is in the soil, parts per million, how much magnesium is in the soil.

We're now coming around to the idea that the living parts of the soil, everything that's burned off when they put the sample in a furnace, often, the living parts of the soil are really super-important in terms of nutrient uptake for the plant because of these things like these bacteria and the fungi, the mycorrhizal fungi and all the other kinds of beneficial fungi that live in soil.

So, yeah, I think we're really coming around to the idea that we can't just reduce it down to how many parts per million of this element or that element. There's way more to soil than just the inorganic matter that is available to plants.

Jane Perrone 0:17:01.8

Absolutely. It's all about what's going on below ground. I like looking at the beautiful stuff. Probably this is a minority, but I'm sure you're the same - I love getting a hand lens out, having a look at what's happening in the soil and checking out roots because even roots look amazing under a hand lens!

Scott Zona 0:17:22.1

Oh, they do. They do, yeah.

Jane Perrone 0:17:25.3

Yeah, it's another whole thing. It gets very messy though. That's the only thing. My husband's, like, "Oh, gosh. You've been getting plants out again!"

Scott Zona 0:17:31.4

Actually I love rooting a cutting in a glass of water, watching those roots develop. I think it's fascinating.

Jane Perrone 0:17:47.9

More from Scott shortly, but now it's time to hear from our sponsors.

'This week's show is supported by Cozy Earth, the premium bedding company that helps you get the deep, restorative sleep you need. Bedtime is literally my favourite time of day, so it's really important that my bed is the most comfortable place it can be.

I got to try out a set of Cozy Earth sheets and they really are so comfortable. Cozy Earth's high quality bedding is responsibly-sourced and made from soft and sustainable viscose that comes from bamboo fabrics. Bundle up in Cozy Earth pyjamas, made from ultra-soft viscose, from bamboo, this holiday season. Now available in holiday hues. Want to give the gift of a good night's rest with Cozy Earth? On The Ledge listeners can take up Cozy Earth's exclusive offer today. Get 40% off site-wide at cozyearth.com using code LEDGE. That's Cozyearth -- c-o-z-y-earth.com and use code LEDGE. (L-E-D-G-E) for 40% off now.'

Jane Perrone 0:19:07.6

One of the things I wanted to talk about, was the Law of the Minimum. I think this, to me, is one of the keys to understanding houseplant care, for me anyway, in that you can't consider any of the factors, the inputs for the plant's experiencing in isolation - you've got to look at the whole picture. Can you just explain to listeners what the Law of the Minimum is and how it applies to houseplant care?

Scott Zona 0:19:39.7

The Law of the Minimum basically says that - and this was in relation to soil fertility. This was put forth by a German chemist back in the 19th century, Baron von Liebig -- so, it's Liebig's Law of the Minimum that plant growth is limited not by the average fertility of the soil, or the general facility, but it's limited by the one nutrient that is in lowest supply.

This is the diagram in the book. Think of a half-barrel with staves of different lengths, and each stave represents one of the nutrients that plants need to grow. Growth can be thought of as the amount of water that you can hold in that half-barrel. Obviously, the water will rise until it hits that shortest stave, and then it begins to overflow. It's that shortest stave, that one nutrient that's in limiting supply, that's what limits plant growth, not the general fertility of the soil or the overall fertility. And in fact, if we were looking at, say, phosphorus in the soil, and we say, "Oh, well, this soil has got lots of phosphorus, so this plant should grow really well", well, yeah, but if the limiting factor is nitrogen, then you can add all the phosphorus you want and it's not going to increase growth if we're looking at the wrong nutrients.

We can also think of this law applying to plant growth generally. So if we talk about light as being also something that could be limiting, or water could be limiting. So all of these things, as you say, you have to think of them holistically - all happening all at once. We can't just think of things working in isolation because that's not how things work.

Jane Perrone 0:21:41.8

As you say, the original principle was nutrients, but I think it applies so brilliantly to light because people are, like, "Why is my plant rotting?" They think it's because there's too much water. Well, it is, but it's also because the plant's slowed down to zero on the photosynthesis front because it's so dark that the water is not being used.

I imagined it as like a set of things connected by strings, where if you pull one thing, it's affecting the other thing. So that's why, in a way, it's so complicated to try to give answers to questions, because you're, like, "Well, yeah, that is a problem!"

Scott Zona 0:22:20.6

Exactly.

Jane Perrone 0:22:21.1

I guess it's the same with animal medicine, or anything. These things are complex. You can't just say, "Well, you've put too much water on your plant," or "You haven't given it enough water." Well, that's connected to temperature and light and relative humidity, etc, which is also obviously tied into temperature, and so on and so forth.

Scott Zona 0:22:45.4

Yeah, it's all inter-related.

Jane Perrone 0:22:46.7

Is there anything, from your point of view, from the book, that you hope people will have one major takeaway?

Scott Zona 0:22:54.3

Actually, I think exactly what you were just saying, about how everything is connected as if by strings. I think the interconnectedness of plants in the natural world, I think is really what I'd love people to take away from this. Plants are not these isolated creatures that just pop up here and there, that there's all this connectedness underground. We've been talking about mycorrhizae and all the underground biome, the microbiome of plants underground, but also, of course, the relationship with pollinators, the relationship with herbivores. It's that interrelatedness of everything that is, to me, so amazing and maybe something that people don't think about so much.

Maybe if they read the book they'll come away with that. So yeah, if I had to say one thing, that's my answer -- the interconnectedness of the natural world.

Jane Perrone 0:23:57.8

Well, I think that's a great answer. We've already mentioned about stuff we don't know. You must have come across things where you think, "Oh, well, that's a black hole. We don't know the answer to that one"? If there's one thing that you could find out before you die kind-of-thing, is there one sort of botany mystery that you'd like solved?

Scott Zona 0:24:20.6

Yeah...

Jane Perrone 0:24:21.7

Putting you on the spot here, the Holy Grail!

Scott Zona 0:24:26.9

Gosh! Here we are banging on about roots again. I'm going to bang on about the microbiome. As I was doing the research for the book, the whole microbiome of plants is something that's a really hot field of research right now, and something that 20 years ago nobody thought of. If anything, bacteria or fungi were bad and they should be got rid of and then the plant will grow better. And now we're realising that it's quite the opposite.

There was a book that came out -- and now I'm blanking on the name of the book -- about the microbiome of humans. So all the bacteria and other micro-organisms that live in and on humans, and how most of them are either neutral or beneficial, but a few of them, of course, can cause disease. It was a really interesting book. It was a New York Times bestseller for a while.

Humans, of course, are going to be the first area of that kind of research, obviously, and I think we're just now turning our attention to plants and seeing how important the microbiome of plants is. And this, again, 20 years ago, nobody was even thinking about this and now there's so much going on. I've mentioned already the rhizobacteria, but also, there are endophytes. These are microbes that live inside plants and, again, often have beneficial effects. Some are probably neutral in their effect, but some have beneficial effects. That was not realised until very, very recently. If you saw a microbe inside a plant, you immediately assumed it was pathogenic and bad and had to be killed. But we're now realising that's not the case.

So I think that's definitely an area where we're going to see lots of research coming out in the future. It'll be a while before it gets too focused on houseplants. I think, right now, the research is all focused on crop plants. Obviously, wheat and soya bean and corn, and then maybe it will eventually get to ornamental plants, like petunias and snapdragons, but eventually, it will get to the level where they're looking at houseplants and the microbiome of houseplants. I think that's going to be a revelation.

Jane Perrone 0:27:05.4

Yeah, absolutely. I'm Googling while you were talking there, the name of the book. Was it "I Contain Multitudes' by Ed Young?

Scott Zona 0:27:13.2

Yes, that's it.

Jane Perrone 0:27:14.8

I just Googled 'Human Microbiome + bestseller,' and that came up, so I'm thinking that was it.

It looks really interesting and then you realise that, basically, there's less human of you than there is microbe and then it starts to blur! Yeah, it's amazing. Absolutely amazing! I can read that once I've finished the Merlin Sheldrake fungus book - have my mind blown even further!

Well, it's fantastic to hear about this new book. I rarely do blurbs for the back of books, but I really wanted to do it for this one because I just feel really excited for people to have a chance to have a look at this and have their eyes opened. I feel like I've got a reasonable understanding. I've got an RHS qualification, not a particularly high one, but I've done some study, but I learnt absolutely loads, and it was just fascinating to read. So I hope some listeners will take a look at this and get their hands on it, just to help their understanding of plants more widely. I'm sure it will help people treat their plants better as well. So thank you very much, Scott.

Scott Zona 0:28:26.9

I hope so. Thank you.

Jane Perrone 0:28:35.9

Thanks so much to Scott, and do check out the show notes at janeperrone.com for details of where you can buy Scott's new book and also a useful diagram of the plant construction Lego metaphor that we spoke about at the start of the interview. And if you always ignore me saying "Go and look at the show notes!" I really would go and look at the show notes because you will also find transcripts of older episodes. So if you're the kind of person that wants to check exactly what somebody said, or perhaps you prefer to read, rather than listen, or perhaps you know someone who is hard of hearing and may want to enjoy the show through the transcript, then that is what that transcript is there for - to make the show as accessible as possible to everybody. So do go and check that out. I put a lot of work into those show notes, so I'd love you to take a look at them.

Hat tipped to my Patreon subscribers this week, that's Hyda, Patricia and Laura who became Ledge Ends and Abby, who became a Crazy Plant Person. I currently have a sore hand from writing out my Patreon cards going out to those at the Ledge End and Superfan level. More details about that in the show notes.

Time for a quick Q & A before we go. You may remember, back in Episode 240, Rowena was asking about Fluval Stratum and I gave a few details about how I use this substrate, which is originally designed for aquariums.

Frank got in touch to tell me about his experiences. I think Frank's in Sweden actually. Frank's been using Fluval Stratum for about a year and a half, for rooting cuttings and, apparently, there is a Facebook group called 'Growing in Stratum' which I will link in the show notes for you. I think I'm going to be joining that one too. Frank's had a lot of success rooting cuttings. He describes cuttings as doing astonishingly well. Frank's technique is to have a layer of leca in a small jar, then stratum on top with a cutting either stuck into or laying on the stratum. The water level should always cover the leca, ie, almost up to the stratum. I don't think it works as a substrate for adult plants. Maybe it can also be used for growing some kinds of plants from seeds, but I have not tried that?

Frank suggests using small jars for propagation because Fluval Stratum is quite expensive, and also notes that the balls crumble easily when wet. So once the plants develop roots, Frank uses a pin, or the like, to loosen the stratum around the roots, take the plant out and let the stratum dry out. Once it has done that, it and the leca can be removed from the jar and eventually be reused. That seems to work a few times until you need to use a new batch of stratum. Frank notes that some people do mix old stratum with ordinary substrate, to avoid wasting it, but that's not something that he has yet tried.

So I hope that's a useful insight and if anyone else has anything useful to tell me about Fluval Stratum, well, me and Rowena and anyone else who would like to know, please do drop me a line to <ontheledgepodcast@gmail.com data-preserve-html-node="true"> That's also where you can send your questions.

That is all for this week's show. Don't forget this time next week I will be at the British Library doing a live-stream and live appearance as part of the Indoor Jungle's panel discussion, along with Tony Le-Britton, Mike Maunder and Carlos Magdalena. So please do check the show notes to book your place on the live-stream, or in person ticket, that's happening on December 2nd 2022.

For the meantime, have a great week, make sure your plants have a great week and I'll see you next Friday. Bye!

The music you heard in this episode was Roll Jordan Roll, by the Joy Drops, The Road We Used To Travel When We Were Young, by Komiku, and Enthusiast by Taught. The ad music is Holiday Gift, by Kai Engel. All tracks are licenced under Creative Commons. Visit the show notes for details.

Subscribe to On The Ledge via Spotify, Apple Podcasts, Player FM, Stitcher, Overcast, RadioPublic and YouTube.

Dr Scott Zona joins me to talk about his new book, a Gardener’s Guide to Botany, plus I get some feedback on Fluval Stratum.

Patreon subscribers at the Ledge End and Superfan level can listen to An Extra Leaf 101 where Scott talks about plant species that collect leaf litter. You can listen to the other episodes in the On The Ledge botany series here.

This week’s guest

Dr Scott Zona is a botanist, researcher, and educator with a focus on tropical plants: you’ll find him on Instagram as @scott.zona and on Twitter as @Scott_Zona. For 9 years he served as the curator of the Wertheim Conservatory and Greenhouses at Florida International University in Miami, where he directed the restoration of the conservatory and maintained their research plant collections. Dr. Zona has collaborated with scientists worldwide on plant ecology research and has taught graduate- and undergraduate-level courses on tropical plant taxonomy. He guides garden tours and workshops for students, garden clubs, and the general public. In addition, he was a palm biologist with the Center for Tropical Plant Conservation at the Fairchild Tropical Botanic Garden in Florida. He also educates houseplant enthusiasts through his online course, The Botany of Houseplants.

You can also hear Scott talking about palms in episode 63 of On The Ledge Podcast.

Scott’s book A Gardener's Guide to Botany published by Cool Springs Press is out December 6 2022.

Dates for your diary

On December 2 2022, I'm taking part in a panel discussion on houseplants at the British Library, along with James Wong, Carlos Magdalena and Mike Maunder. Indoor Jungles: The Story of the Houseplant starts at 7pm, and livestream and in person tickets can be booked here.

Useful info while you listen…

The diagrams below illustrates phytomers, the repeating units of plants that are above ground: each consists of a leaf, a node, and an axillary bud as well as the internode. Scott uses the analogy of a lego set to illustrate how this works.

The fungi book I mention is by Entangled Life by Merlin Sheldrake. The book Scott mentions that explains the human microbiome is I Contain Multitudes by Ed Yong.

Liebig’s law of the minimum is a really useful concept to understand if you are growing plants: growth is dictated not by total amount of resources available to the plant, but by the limiting factor - ie the resource that is most scarce.

QUESTION OF THE WEEK

Frank offered up some information on Fluval Stratum as a substrate for houseplants in answer to Rowena’s question about this product in episode 240.

Frank says:

Rooting cuttings in it generally works very well. Astonishingly well, I’d say. What I usually do is to have a layer of leca in a small jar, and then stratum on top, with the cutting either stuck into or laying on the stratum. The water level should almost cover the leca, i.e., almost up to the stratum. I don’t think it works as a substrate for adult plants. Maybe it can also be used for growing (some kinds of plants) from seeds, but I have not tried that.

Examples of plants I propagated in it are Operculicaryas, Boston fern, och Brunfelsia. There have been more, like Scindapsus pictus, but those three I had been struggling with a lot until stratum came along.

Since it’s rather expensive, you want to use small jars for propagation. Also, the small balls it consists of crumble easily when it’s wet. Therefore, once a plant has developed roots, I usually just use a pin or the like to loosen the stratum around the roots, take the plant out, and then let the stratum dry out. Once it has done that, it (and the leca) can be removed from the jar and eventually be reused. That seems to work a few times until you need to use a new batch of stratum. Apparrently some people mix old stratum into their ordinary substrate to avoid wasting it, but I have no experience with that because I have not yet had any that could not be reused for propagation.

The Facebook group Frank mentions is called Growing in Stratum.

If anyone else has feedback of Fluval Stratum do get in touch!

Want to ask me a question? Email ontheledgepodcast@gmail.com. The more information you can include, the better - pictures of your plant, details of your location and how long you have had the plant are always useful to help solve your issue.

THIS WEEK’S SPONSOR

COZY EARTH

This week’s show is supported by Cozy Earth, the premium bedding company that helps you get the deep restorative sleep you need. Bedtime is literally my favourite time of day, so it’s really important that my bed is the most comfortable place it can be. I got to try out a set of Cozy Earth sheets and they really are so comfortable! Cozy Earth’s high quality bedding is responsibly sourced and made from soft and sustainable viscose that comes from bamboo fabrics. Bundle up in Cozy Earth pajamas made from ultra-soft viscose from bamboo this holiday season. Now available in holiday hues! Want to give the gift of a good night's rest with Cozy Earth? On The Ledge listeners can take up Cozy Earth’s exclusive offer today - get 40% off site wide at cozyearth.com using code LEDGE now.

HOW TO SUPPORT ON THE LEDGE

Contributions from On The Ledge listeners help to pay for all the things that have made the show possible over the last few years: equipment, travel expenses, editing, admin support and transcription.

Want to make a one-off donation? You can do that through my ko-fi.com page, or via Paypal.

Want to make a regular donation? Join the On The Ledge community on Patreon! Whether you can only spare a dollar or a pound, or want to make a bigger commitment, there’s something for you: see all the tiers and sign up for Patreon here.

The Crazy Plant Person tier just gives you a warm fuzzy feeling of supporting the show you love.

The Ledge End tier gives you access to two extra episodes a month, known as An Extra Leaf, as well as ad-free versions of the main podcast on weeks where there’s a paid advertising spot, and access to occasional patron-only Zoom sessions.

My Superfan tier earns you a personal greeting from me in the mail including a limited edition postcard, as well as ad-free episodes.

If you like the idea of supporting On The Ledge on a regular basis but don't know what Patreon's all about, check out the FAQ here: if you still have questions, leave a comment or email me - ontheledgepodcast@gmail.com. If you're already supporting others via Patreon, just click here to set up your rewards!

If you prefer to support the show in other ways, please do go and rate and review On The Ledge on Apple Podcasts, Stitcher or wherever you listen. It's lovely to read your kind comments, and it really helps new listeners to find the show. You can also tweet or post about the show on social media - use #OnTheLedgePodcast so I’ll pick up on it!

CREDITS

This week's show featured the tracks Roll Jordan Roll by the Joy Drops, The Road We Use To Travel When We Were Kids by Komiku and Enthusiast by Tours. The ad music is Holiday Gift by Kai Engel.